By Dr. Deng Bol Aruai Bol

This week, a 3-minute, 39-second audio message from Mr. Edmund Yakani, the Executive Director of the Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO), was shared widely among the public. In it, Mr. Yakani raised serious concerns about growing incidents of bullying, mockery, and verbal abuse targeting persons with disabilities in South Sudan.

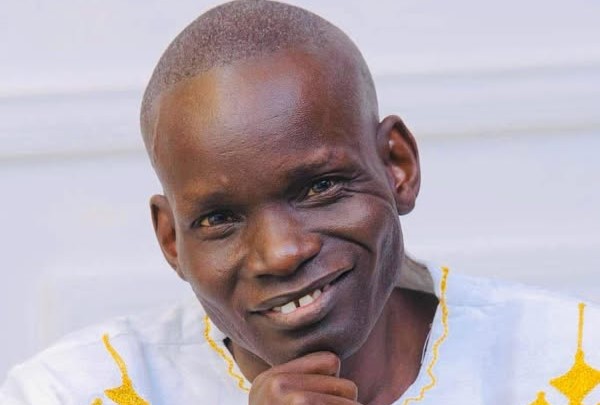

Although no specific names were mentioned, the message came at a time when I, as a citizen living with a disability, have been subjected to insults, humiliation, and dehumanizing remarks simply because I expressed my desire to run for the presidency of the Republic of South Sudan. What Mr. Yakani did, knowingly or unknowingly, was to echo the silent pain so many of us have carried alone. His words pierced through the noise, reminding this nation that silence in the face of injustice is complicity, and that every citizen, no matter their physical ability, deserves to be treated with dignity.

Mr. Yakani’s statement is not just a civil society message. It is a strong and principled stand for dignity, equality, and the rule of law. In his message, he reminded the public that persons with disabilities are protected not only by the Constitution of South Sudan but also by international instruments that South Sudan has ratified, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). He stressed that the Bill of Rights enshrined in our Transitional Constitution affirms that every citizen—regardless of ability—has the right to participate fully in public life, including the right to seek elective office.

He was not making a political argument; he was reminding the country of its legal obligations. When he said, “The Constitution of South Sudan and the UNCRPD that President Salva Kiir Mayardit signed into law are very clear,” he was pointing us back to the foundational promises that hold this nation together.

“The Constitution of South Sudan and the UNCRPD that President Salva Kiir Mayardit signed into law are very clear,” Yakani stated. “No person should be bullied, discriminated against, or insulted based on their disability. If this continues, civil society may resort to legal action.” This is not just a warning. It is a call for accountability.

A reminder that the South Sudan we are building must be a country where every citizen counts, and no one is silenced for daring to dream big. In that audio, you could hear the seriousness of a man who has seen far too many cases of abuse go unanswered. And in his appeal to the Ministry of Gender, Child and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Justice, Yakani was drawing a line. A line that says: if the system does not respond, then the people will. And that, in its truest sense, is what civil society is for.

What happened to me over the past weeks is known by many. After publicly stating that I intended to contest the presidency, I was attacked—not for my policies, not for my ideas, but for my physical condition. I was mocked, ridiculed, and demeaned by individuals who believe disability disqualifies someone from leadership. These insults were not just personal.

They were a reflection of a dangerous mindset—one that suggests that political participation is a privilege reserved for the able-bodied. That is wrong. And it must be challenged. Not just for me, but for everyone who has been made to feel ashamed, excluded, or inferior because they were born different or walk a different path. I have been called names; I have been told to sit down and stay quiet—but I will not. Because the right to dream and lead belongs to all of us.

I was not born a politician. I am a scholar, an advocate, and a citizen who believes that South Sudan deserves better. Like any other citizen, I have the right to speak, to contest, to lead, and to contribute to the future of my country. My disability is not a weakness. It is a part of who I am—and it is a perspective that has shaped my leadership, not limited it. No one should ever be told that they are “less” because they move differently, speak differently, or look different.

That is not who we are as South Sudanese. That is not who we must become. If we are to move forward as a nation, we must make room for all voices, including those that society too often overlooks. This is not a plea for sympathy—it is a demand for equality, grounded in the law and in our shared humanity.

The Constitution of South Sudan (2011) is very clear under Article 30(1): “All persons with disabilities have the right to enjoy all the rights and freedoms set out in this Constitution, especially the rights to dignity, personal integrity, and participation in public life.” Article 16 of the UNCRPD, which South Sudan ratified in 2023, prohibits all forms of exploitation, violence, and abuse against persons with disabilities, including psychological harm