When South Sudan’s Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, Joseph Geng Akech, signed the order to reopen Juba’s Freedom Hotel, he described it as a matter of law, correcting what he called an “unnecessary and unlawful” closure.

But for the family of the three sisters who died there in March, the decision has reopened not a business, but old wounds.

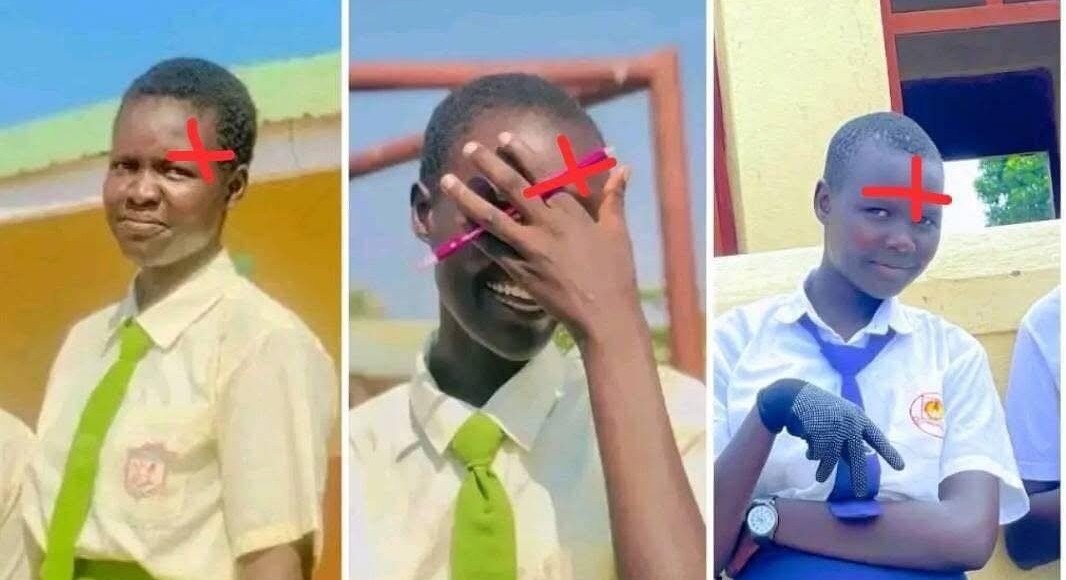

The tragedy of Achol Waat Arol (21), Achol Chol Arol (19), and Abeny Chol Arol (15) remains one of the most haunting cases in Juba this year.

The sisters were found dead in their hotel room on March 28, and initial police findings suggested that a toxic chemical or gas was released through the air-conditioning system.

Months later, the cause of death and accountability remain mired in legal and institutional uncertainty.

In his order, Minister Geng argued that the continued detention of the hotel owner and staff had “no legal basis” under South Sudan’s penal code, noting that investigations were completed and forensic results from Nairobi had been received in June.

“I cannot find any legal reasons for the hotel to remain closed,” he wrote, insisting the suspects’ rights had been violated by prolonged detention beyond the three-month legal limit.

The decision highlights the legal tightrope between due process and public sentiment, a recurring dilemma in South Sudan’s justice system.

On one hand, the minister’s action reflects a growing emphasis on procedural integrity and judicial independence; on the other, it risks deepening the public’s crisis of trust in institutions that often appear indifferent to victims.

For the family of the deceased, the decision feels premature and painful.

Their lawyer, Josephin Adhet Deng, accuses authorities of ignoring unresolved evidence and possible tampering with the hotel’s air-conditioning system.

“Justice cannot move forward when parts of the evidence were replaced during investigation,” she said, calling the reopening “a betrayal of truth.”

The family patriarch, Chol Arol, who lost all three daughters in a single night, says the government’s decision sends a dangerous message: that commercial interests can outweigh human life.

“The hotel reopens, but our pain and questions remain,” he was quoted.

Legal experts note that the case, now registered as Criminal Case No. 2174/2025 — could set a precedent for how South Sudan handles sensitive criminal cases involving private businesses and state oversight.

It emphasizes the challenge of balancing the rule of law with the emotional demands of justice in a country still rebuilding its legal framework after years of conflict.

As Freedom Hotel reopens its doors, the families of the victims say justice remains locked away, not in the courtroom, but in a system where truth and accountability often take different paths.