The Rumbek Youth Union in Juba has renewed calls for justice over the brutal killing of the three daughters of General Chol Arol Kelueljang, describing recent government actions as “an obstruction of justice” and “a betrayal of public trust.”

The youth’s appeal comes in response to the decision by Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister Joseph Geng Akech to release suspects on bail and reopen the Freedom Hotel the crime scene where the three sisters lost their lives in March this year.

“Justice delayed is justice denied,” said Lino Laat Nuer, Chairperson of the Rumbek Youth Union.

“Dr. Geng’s actions threaten peace and stability, and have shaken public confidence in the justice system.”

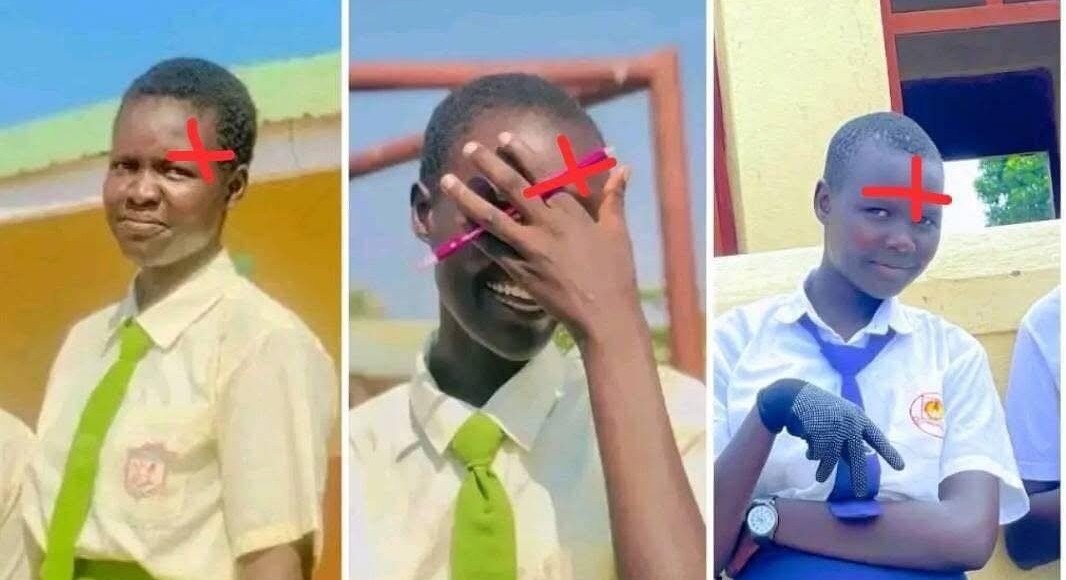

The killing of Achol Waat Arol (21), Achol Chol Arol (19), and Abeny Chol Arol (15) remains one of Juba’s most chilling tragedies in 2025.

The three sisters were found dead in their hotel room at Freedom Hotel on March 28, with initial police reports suggesting they were killed by exposure to a toxic chemical or gas possibly released through the air-conditioning system.

Despite early investigations and forensic samples reportedly sent to Nairobi, the cause of death remains clouded by legal and institutional uncertainty.

Last month, Minister Geng signed an order reopening Freedom Hotel, calling its previous closure “unnecessary and unlawful.”

In his order, he stated that investigations were concluded and that the continued detention of the hotel owner and staff had “no legal basis” under South Sudan’s penal code.

“I cannot find any legal reasons for the hotel to remain closed,” the minister wrote, arguing that suspects’ rights had been violated by prolonged detention beyond the three-month legal limit.

The minister’s decision underscores the delicate balance between due process and public sentiment in South Sudan’s justice system.

While his move signals a commitment to procedural integrity, it has reignited widespread anger among citizens who see it as a denial of justice for the victims.

Family lawyer Josephin Adhet Deng accused authorities of ignoring unresolved evidence and possible tampering with the hotel’s air-conditioning system.

“Justice cannot move forward when parts of the evidence were replaced during investigation,” she said, calling the hotel’s reopening “a betrayal of truth.”

For Gen. Chol Arol, the father of the three girls, the reopening of Freedom Hotel feels like reopening old wounds.

“The hotel reopens, but our pain and questions remain,” he lamented. “The government’s decision sends a dangerous message — that commercial interests can outweigh human life.”

Legal experts note that the case — registered as Criminal Case No. 2174/2025 could set a precedent for how South Sudan handles sensitive criminal cases involving private businesses and state oversight.

It highlights the country’s ongoing struggle to balance the rule of law with the emotional weight of justice in a fragile post-conflict legal system.

As the Freedom Hotel resumes operations, the families of the victims and the Rumbek youth community say justice remains elusive not locked in the courtroom, but in a system were truth and accountability too often part ways.